Käthe Kollwitz and the Afterlife of Compassion

Some images do not seek attention. They wait, carrying the weight of what has already been endured.

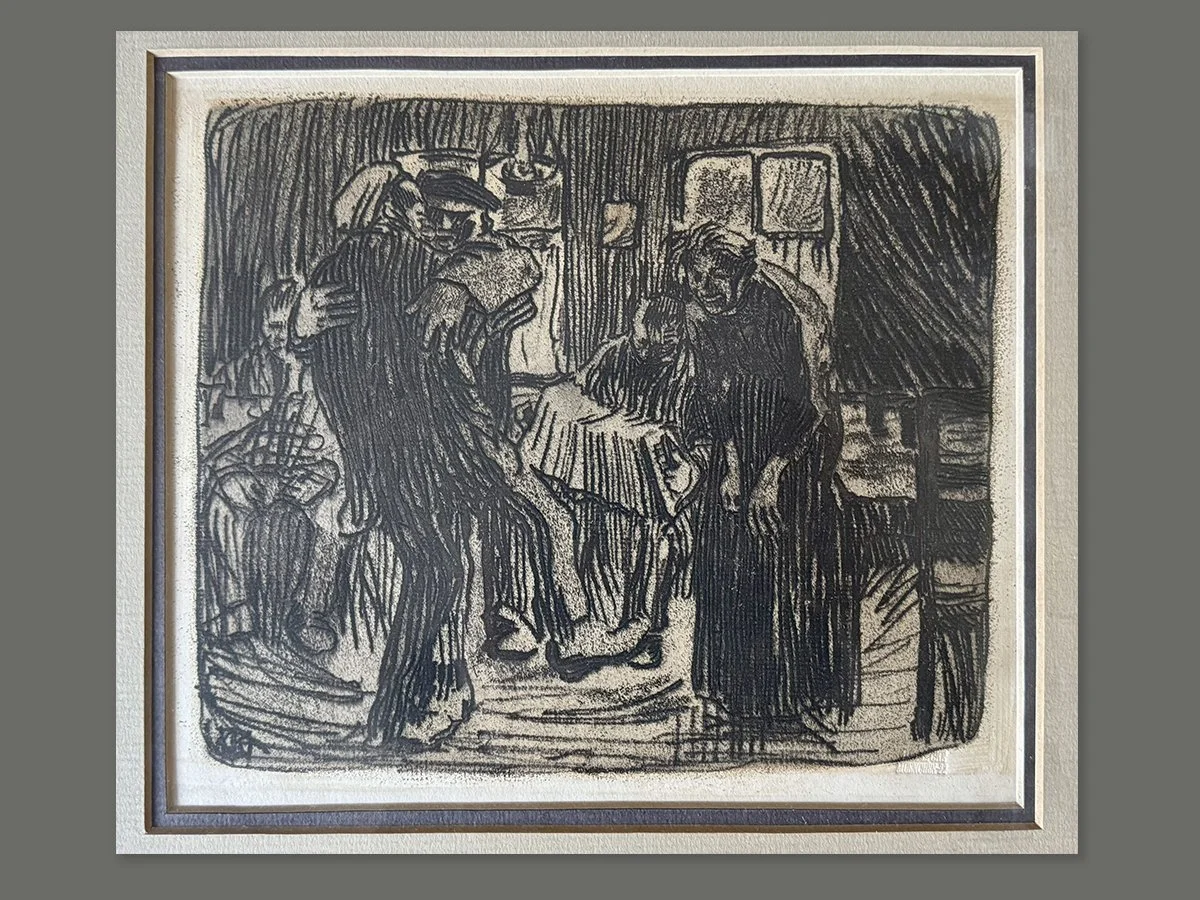

In an age that prized surface, Käthe Kollwitz pressed emotion into depth. Born in 1867 in Königsberg, she worked not in color but in pressure, carving human experience into copper until compassion itself left a mark. Her Hamburg Public House (1901) depicts working men gathered at wooden tables, exhaustion and fellowship registered not through expression, but through posture. Nothing in the scene is elevated. Nothing is embellished. Yet everything in it remains.

Kollwitz’s process mirrored the ethics she lived by. Each line began as resistance, a tool pressed into the plate until it remembered the weight of her intent. Meaning was not added afterward. It was formed through contact. Pressure accumulated. Marks remained. What endured was not surface, but what had been asked of the material again and again.

To step into the print is to enter a room shaped by use rather than display. Figures gather as if around a table while silence settles into the corners. In Hamburg Public House, the grain of the benches and the slouch of the patrons suggest a familiarity that borders on sacred. It is a social architecture, humble, communal, and profoundly human, shaped by shared presence and the quiet labor of daily life.

Objects shaped by time carry knowledge in the same way. They register repetition, return, and restraint. What survives is not the polish of a moment, but the accumulation beneath it.

As Europe darkened under fascism, Kollwitz’s work endured through quiet stewardship. American women, teachers, librarians, and members of the American Association of University Women, carried her prints into school libraries and small towns far from major galleries. The press called her “the greatest woman artist of modern times,” but what endured was not the title. It was the humanity held in her hand.

The Hamburg Public House restrike bears the faint embossing of its plate mark, a subtle indentation recording the pressure beneath its surface. It is not flaw, but evidence. Proof of contact. Proof of care.

It is this understanding of endurance, where care becomes visible over time, that guides the objects placed back into circulation at Acanthus Home. Here, the heirloom is understood less as an object than as a conversation between generations about how to see, how to hold, and how to remember.

Käthe Kollwitz once wrote, “I want to have an effect on my time.” She did. Yet her effect continues beyond it, wherever care is pressed into matter and allowed to remain.